Third Reich May Day Event Tinnies (1934–1939): A Collector’s Guide

Share

Disclaimer

This article is intended solely for historical and educational purposes. It does not promote or endorse any political ideology, regime, or symbolism associated with the Third Reich. The content presented reflects the historical record and aims to support collectors, researchers, and those studying the material culture of the era with accuracy and neutrality.

Historical context

From 1933, Nazi Germany transformed May Day—traditionally a workers’ holiday—into a highly orchestrated event called the “Day of National Labor”. The purpose was clear: to erase independent labor movements and merge worker identity into the state apparatus of National Socialism. Massive rallies, marches, and cultural events marked the occasion until 1939, when the outbreak of World War II halted such displays.

To commemorate each year’s May Day festivities, event participants were issued decorative pins known as tinnies (Veranstaltungsabzeichen), which served both as propaganda tools and attendance markers.

Event tinnies

May Day tinnies were mass-produced and distributed nationwide. Despite their low-cost construction, the artistic quality and symbolic detail can be quite striking.

The May Day tinnies issued between 1934 and 1939 showcase a fascinating progression in visual propaganda — mirroring broader ideological shifts within the Nazi regime. While the early designs (1934–1936) focused heavily on labour, production, and class unity, the later designs (1937–1939) moved toward cultural, romanticised imagery, often with an emphasis on ethnic unity and territorial expansion.

1934–1936: Industry, Labour, and National Strength

1934 — The industrial citizen

The inaugural May Day tinnie under Hitler glorifies productive labor and presents the worker as central to the new German order. The regime is still courting the working class after dissolving the unions.

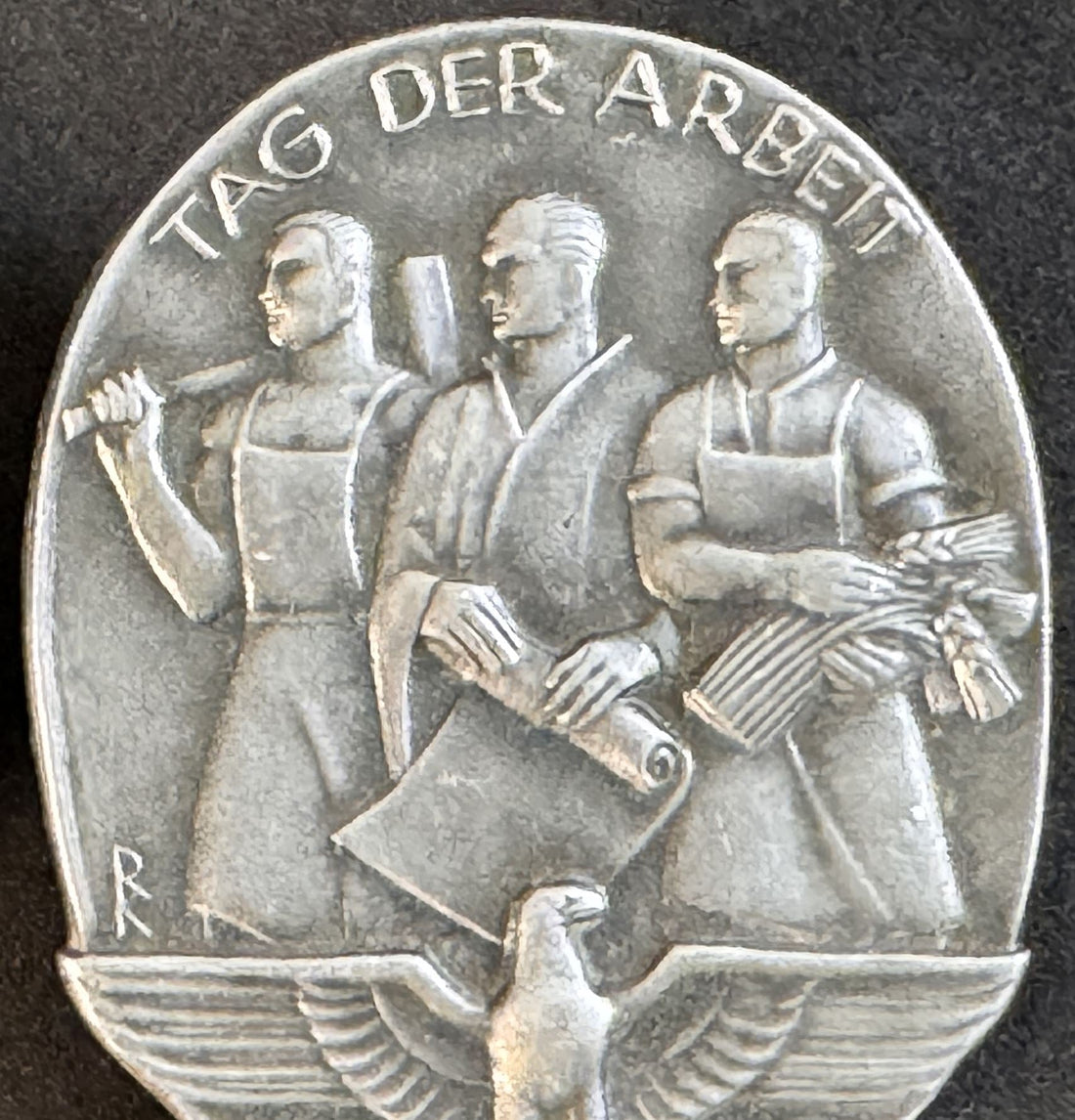

1935 — Worker, scholar, and farmer - the triad of production

Marching workers of agriculture, industry and scholarship. Message: “Mind and body in service of the Reich.”

A refined portrayal of class unity, with symbolic overlap between knowledge and labour. This suggests harmony and ideological education within the workforce, a final nod to intellectual inclusivity before militarisation begins.

1936 — Agriculture to industry to strength and war

The first year the event is termed as "1. Mai" (1st May), no longer "Tag der Arbeit." It now features the weapon motif (sword), fused with agricultural and industrial tools. Message: “The nation must be strong self sufficient.”

Coincides with the reoccupation of the Rhineland and the rise of militaristic imagery. The scholar is gone. Labour and the preparation phase for war are the goals. Domestic propaganda pivots toward martial readiness.

🎭 1937–1939: Culture, Ethnicity, and Expansion

1937 — The Idealised Youth

Youthful figure with a branch or banner. Message: “The future belongs to us.”

The badge reflects romantic nationalism and biological idealism, less about work, more about purity, renewal, and sacrifice. It’s a softening of visual tone, but with a more insidious undercurrent: the shaping of future warriors.

1938 — Maypole dance of tradition and unity

Male and female figures dancing with ribbons around a Maypole. Message: “Joyful tradition, cultural unity.”

Shifting fully away from industrial imagery, this tinnie uses rural symbolism of the Maypole, in which to promote the romantic ideal of a unified, healthy, agrarian-based people. Issued in the year of the Anschluss, it reinforces the regime’s attempt to mask territorial expansion in the language of peace and heritage. The imagery subtly elevates gender roles, fertility, and the celebration of “Greater Germany” through folk ritual rather than force.

1939 — The motherland allegory

A stylised and forward flowing female figure, holding bouquets of flowers. A clear reference to the "Flower Wars" (also known as the “Blumenkriege”). A banner below inscribed with: “OSTMARK – ALTREICH – SUDETENLAND”

(Ostmark = annexed Austria, Altreich = old/greater Germany, Sudetenland = territory seized from Czechoslovakia).

Message: “Germany is whole again."

The use of soft, classical imagery avoids overt militarism. It was carefully crafted to signal righteous unification, not aggression, likely to reassure both domestic and international audiences in the tense months before the invasion of Poland.

Historical note: The “Flower Wars”

The 1939 May Day tinnie is often seen as a commemorative piece celebrating the so-called “Flower Wars”, Germany’s bloodless annexations of Austria and the Sudetenland, which were widely portrayed as joyous homecomings.

The flowers held by the allegorical female on the badge echo the celebrations and public adoration that accompanied German troops as they entered these territories; events that would later be revealed as strategic stepping stones to war in Europe.

You can explore original medals and decorations issued during the Flower Wars era in our German Medals collection.

Materials & Construction

| Year | Material | Finish | Mount | Maker marks (not exhaustive) |

| 1934 | Brass | Lacquered bronze | Pin, soldered |

No.7 Recihsverband Pforzheim Reichsverband, Pforzheim, 47 Ferd. Wagner Pforzheim |

| 1935 | Aluminium | Pin, crimped |

O.W. Schwab.Omund Chr. Bauer Welzheim Ferdinand Wagner, Pforzheim 8 Robinson Oberstein/Nahe E.F. Weidmann Frankfurt a.M.S. Ziemer & Söhne Oberstein/Nahe |

|

| 1936 | Aluminium | Pin, crimped |

Chr. Bauer Welzheim Hoffstatter. Bonn Heinrich Vogt Pforzheim Ochs & Bonn Hanau Deschler & Sohn Munich No. 9 |

|

| 1937 |

Zinc alloy Aluminum |

Blackened (zinc) | Pin, crimped |

Mayer u. Wilhelm Stuttgart Ziemer & Sohn K. Franck Nurnburg Besson Gmund |

| 1938 | Zinc alloy | Blackened | Pin, crimped |

Heinrich Vogt Pforzheim Richard Sieper & Sohne Ludenscheid Erhard & Sohne AG Schawb Gmund Gebr. Lang- Ludenscheid |

| 1939 | Zinc alloy | Blackened | Pin, crimped |

Chr. Bauer Welzheim Ulbricht Wien R. Hasenmeyer Jr - Pforzheim Jakob Bengel Oberstein Meyerwerke Luckenwald |

You can explore original May Day and other Third Reich tinnies in our Brooches and Pin Badges collection.

Conclusion

The May Day tinnies of 1934 to 1939 offer more than collectible appeal — they chart the ideological evolution of Nazi Germany from a regime seeking social cohesion through labor, to one driven by expansionist myth-making. Each badge is a visual snapshot of its time: compact, symbolic, and propagandistically precise. Whether you're collecting for historical research, design interest, or deeper cultural insight, these items offer a tangible narrative of Germany's path toward war.

Interested in collecting related artifacts? Browse original May Day and political tinnies in our Brooches and Pin Badges collection, or explore our German Medals selection for decorations tied to the annexation campaigns of 1938–1939.